Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a recessive genetic disorder which is the most common life-limiting genetic disorder amongst Caucasians. I have written before about how improved management of the disease has led to substantial improvements in life expectancy and quality of life, in large part due to its inclusion in newborn screening programs. More recently, it is becoming increasingly common to also offer pregnant women a genetic test to see if they are carriers of a CF-causing mutation in the CFTR gene. Although the disease affects between 1 in 2,500 and 3,500 live births among Caucasians in the US, due to recessive inheritance, about 1 in 25 Caucasians actually carry a disease mutation. This is because a child must have two copies of a mutated gene in order to develop the disease, so two parents who are carriers have a 1 in 4 chance of having a child with CF: \(\frac{1}{4}\times\frac{1}{25}\times\frac{1}{25} = \frac{1}{2500}\).

When I was pregnant with my second child in 2015, I was offered genetic counseling and carrier testing for CF due to my and my husband’s ethnic backgrounds. (This was not offered to me when we had our first child in 2011; though I was going to a different practice/hospital at that time, based on talking to other folks and my own experience, the number of genetic and other tests being offered to pregnant women definitely increased during that period.) Different ethnicities have different prevalences of CFTR and other mutations, so this was based on our self-reported ethnicities and I assume that if we, say, we were both African-American, we would have been offered carrier testing for sickle-cell disease (a recessive disease which affects between 1 in 365 and 1 in 500 African-Americans) instead.

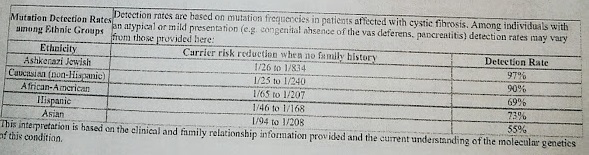

When I got my test result back, this is what it showed:

I do not have any family history of CF, so my chance of being a CF carrier went down from 1/25 to 1/240 (I will be using “Caucasian” and “Caucasian (non-Hispanic)” interchangeably from here on. I am aware that this is not technically correct and that categorizing ethnicity in general is a complex and sometimes fraught endeavor.)… Hmm… I was definitely happy that I my chance of being a CF carrier went down by a factor of almost 10, but as a statistician, I could not help also nerding out on this great application of Bayes’s rule!

Bayes’s rule gives the probability of event B happening given that event A happened in terms of the probability of event A happening given that event B happened. These types of probabilities (B given A and A given B) are called conditional probabilities. Bayes’s rule is usually written as:

\(P(B|A) = \frac{P(A|B)P(B)}{P(A)} = \frac{P(A|B)P(B)}{\sum_{B_j}P(A|B_j)P(B_j)},\)

where \(\sum_{B_j}P(B_j) = 1, P(B_j) > 0\) for any \(j\).

It is often applied in the context of diagnostic testing, which is exactly the context here! If an individual comes in to get tested for a specific disease (or in this case, for being a carrier for a specific disease), you can think of their probability of having it as being the prevalence of that disease in the population they come from. If a 50 year old man asks what his probability of having prostate cancer is, in the absence of any tests or clinical signs, you would usually say that it’s the same as the percentage of 50 year old men who have prostate cancer. If you have more information about them or have a test you can use, then you can update the probability. In this case, my “baseline” probability of being a CF carrier was 1 in 25, since that is the prevalence in Caucasian individuals (Caveat 1: This is an estimate, so the actual prevalence may be somewhat larger or smaller. It also includes all Caucasians and many studies of Caucasians tend to oversample individuals of Northern or Western European origin. I have not looked into this specific aspect in great detail though.)

So we currently have P(Carrier) as 1 in 25, with an implicit conditioning on ethnicity (Caucasian). What the results above are saying is that P(Carrier|Negative test result) = \(\frac{1}{240}\). Abbreviating C = Carrier, - = negative test, we can apply Bayes’s rule to get:

\(P(C|-) = \frac{P(-|C)P(C)}{P(-|C)P(C)+P(-|\mbox{No } C)P(\mbox{No }C)}\)

The “detection rate” of 90% is the probability that the test detects a mutation in someone who is actually a carrier, i.e. \(P(+|C)\) (also known as the sensitivity of the test), among Caucasians. This means that the test is imperfect. Elsewhere in the report, they do state that they only consider 32 common mutations, so it is posible that someone may have a CFTR mutation which is not detected by this test. (Caveat 2: Note also the disclaimer at the top. One question here would be: Why not look at all mutations in CFTR? I can see three reasons here: a) cost b) accuracy - a test for fewer mutations may be more optimized in terms of error rates c) maybe most important - many mutations in CFTR are not in fact disease-causing; in some cases they are known to be benign, but in others, they have “uncertain significance”).

At this point, we know \(P(C) = \frac{1}{25} = 0.04\) and \(P(+|C)=0.90\). This means we also know \(P(\mbox{No }C) = 1-P(C) = 0.96\) and \(P(-|C) = 1-P(+|C) = 1-0.90 = 0.10\). In order to get \(P(C|-)\) with Bayes’s rule, we just need \(P(-|\mbox{No }C)\), also known as the test specificity. In this case, I actually think the test specificity is 1, or 100% (or very close to it). This means that individuals who are carriers should never get a positive test. Going back to the equation, we get:

\(P(C|-) = \frac{P(-|C)P(C)}{P(-|C)P(C)+P(-|\mbox{No } C)P(\mbox{No }C)} = \frac{0.10 \times 0.04}{0.10 \times 0.04 + 1 \times 0.96} = 0.00415\)

This is very close to \(\frac{1}{240}=0.00417\), so it may well just be a difference in rounding or it may be that \(P(-|\mbox{No }C) = 0.995\) instead of \(1\).

So there you have it! I really think this is one of the best examples of the idea of pre-test and post-test probability of having a specific health outcome or disease.

Three final notes:

Note 1. The detection rate is also dependent on ethnicity and is presumably meant to maximize the test performance for the ethnic groups with highest prevalence, namely Ashkenazi Jewish and Caucasian (non-Hispanic). Note that an African-American individual would have an initial probability of 1 in 65 of being a carrier, about 2.5\(\times\) lower than that of an Ashkenazi Jewish or Caucasian individual, but the detection rate for African-Americans is only 69%. After a negative test the probability of being a CF carrier goes down to 1 in 207, which is higher than the 1 in 834 in for the Ashkenazi and 1 in 240 for the Caucasian populations.

Note 2. While a probability of being a CF carrier of 1 in 240 is pretty low, note that the probability of a child having CF with, say, two Caucasian parents without a history of CF, and one of them having had this test and testing negative, is even lower, at \(\frac{1}{4}\times\frac{1}{25}\times\frac{1}{240} = \frac{1}{24,000}\). However, while a positive test would result in a probability of being a CF carrier of 100%, a negative test can never result in a probability of 0%.

Note 3. This is all based on estimates of both the prevalences within ethnic groups and also the properties of the test. I assume that the robustness of the test has been checked in various ways, but it does include the disclaimer at the bottom “This interpretation is based on the clinical and family relationship information provided and the current understanding of the molecular genetics of this condition.”